One night a few weeks ago, I saw something on TV that truly disturbed me. It was a scene from the new television series The Following, a show about a cult of serial killers and their leader (I know that’s a vague synopsis, so if you’re really interested look here.) Now, I don’t regularly watch the show, but I’ve stumbled upon it a few times in between channel surfing and leaving the TV on at night as I work around the house. Most of the scenes I’ve seen so far have been sort of silly or just plain far fetched, and the acting is mediocre at best. I’ll put it this way: I’ve never stayed on the channel for more than a few minutes.

But the scene I witnessed that night is something I won’t soon forget. It made me feel shocked, disgusted, and then, somewhat unexpectedly, genuinely mad. Angry. At the world, and at this unethical, insensitive, and just plain careless show.

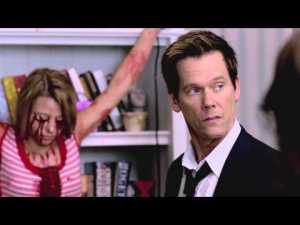

Here’s the brief version of what I can’t un-see: It’s night time, and two male serial killers are standing behind a parked car. The trunk is open. Inside, a gagged and bound woman is laying on her side, crying and pleading for her life. The men are casually watching her as they go back and forth about who should be the one to kill her. It comes out that one of them ( a serial killer wannabe, I guess) has not actually killed someone by himself before, so the veteran killer pushes him to make this this woman his first kill. The newbe, however, cannot bring himself to do it, so the other guy grabs the knife from him. He laughs and makes fun of him, and we get the impression that he thinks the new guy is “too weak” or “not man enough” to follow through with the murder.

At this point, I thought for sure that the show would cut to a new scene, that we wouldn’t, of course, see what it usually left to the imagination on a prime time cable television show. Call me naive, but I’m used to murders being walked in on after the fact, the specifics surveyed only later in crime scenes and on lab tables. But if this scene is any indicator of future ones, The Following is taking TV murder–and specifically, the witnessed killing of women–to a whole new level. So instead of hearing what exactly happened to this victim in all-business conversations between medical examiners and forensic specialists, I saw it for myself.

I watched as the killer approached the woman, who was really hysterical by this point, and excitedly (yet rather unceremoniously, which may have been another reason why it was so disturbing) stab her over and over and over again. Although he stood in front of her as he stabbed her, viewers could not only see blood spray and soak her shirt, but also hear nauseating cutting sounds. I immediately felt sick and to be honest, a little traumatized.

After getting over the initial shock of watching a woman die (the entire scene was maybe a minute and a half, and yes, I was frustrated with myself for watching the whole thing), I started to feel a different emotion: anger. It’s days later and I’m still angry. And no, I’m not willing to let it go.

First off, I’m angry that there is still a mainstream appetite for violence against women. Every victim that I’ve seen so far on this show has been female. The serial killers themselves are both male and female, but they abduct, torture, and kill women. I admit that my exposure to the show is limited, but what clips I’ve seen have had a heavy presence of female victimization.

Is this unusual in movies and shows about murder? Perhaps not, but on a mainstream channel at a not-too-late hour of the night, I’d expect much milder violence. Certainly not full murder scenes. Certainly not horror-movie quality torture and suffering. And certainly not any of these things to a character who I genuinely feel for. In that brief moment, I felt her fear, and even though she was just a TV character, I feared for her. The problem, I think, is that the scene was much too real. I related to her, and imagined myself in her situation. Why? Because murders like that really happen. The scene was too close to what really happens to thousands of women each year.

In light of recent cases like the chilling trial of the Cannibal Cop and this chef who was found guilty of boiling his wife’s dead body, I’m so, so tired of seeing and hearing about men who get off on not just abusing women, but on torturing them. On shooting, strangling, and stabbing them, and then of disposing what remains of these daughters, sisters, and mothers like trash. It pisses me off that it’s acceptable to nonchalantly watch these real-life horrors re-enacted on TV. What’s more, it scares me. It deeply concerns me that our culture is so desensitized to the murder of women that we can sit down on our sofas and enjoy seeing it played out over and again. And then, that we can defend it.

I won’t make the mistake of watching men hurt women on The Following again. I do have to wonder about the writers of this show, though. Who are they, and what’s their agenda? Because if you were to ask me, it seems like they’re interested in showcasing–and encouraging–a culture of misogynistic violence.